Blog

-

-

Regional Industry Sr. Manager Latin America & the Caribbean, IFC

-

-

Country Manager Andean Region, IFC

Nov 29, 2021

This is what heartbreak looks like on social media: “I know of a woman and her daughter who are at risk. Her partner beats them and threatens to kill them.”

Or this: “I’m a single mother of a disabled child. I am out of work, I’m not getting unemployment benefits, my health insurance was suspended… my child requires care and medicine. What can I do?”

Or this: “Between the lockdown, the time since I’ve seen my family, dealing with my teenaged daughter and her schooling, my work overload, and the daily cooking, I am going crazy. For real.”

It’s raw and honest emotion, on full public display. And it’s just a tiny fraction of the millions of such social media conversations taking place among women in Bogotá, Colombia, during the covid-19 pandemic.

These comments could have come from women anywhere in the world. From overseeing their kids’ virtual schooling to tending elderly family members, women everywhere have disproportionately shouldered covid-time caregiving responsibilities. In the United States, for example, 65 percent of low-income working women had to take unpaid sick leave because their children’s school or daycare was closed.

In Bogotá, where 91 percent of these so-called “unpaid caregivers” are female, an astounding 80 percent of these women reported feeling heavily affected by care burdens during the pandemic, a recent IFC study found. IFC was brought in by this progressive city, which has prioritized gender-inclusive city planning as part of its strategic vision for the future, to help them as they rolled out a new social support program, the City Care System. The program is designed to relieve caregivers’ burdens, rebalance caregiving responsibilities, and change cultural norms to elevate the value of the work.

But city officials faced a dilemma: How to understand in more granular detail the pandemic’s differentiated effects on women, so they could optimize inclusive recovery-related policies and programs. They also wondered about the effectiveness of their digital engagement with citizens throughout the pandemic.

This was the basis of a study IFC conducted for the city of Bogota during a nine-month period, September 2020–May 2021. The study was implemented as part of IFC’s LAC Cities Program in partnership with the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs of Switzerland (SECO) and the Government of Korea. Previously IFC has partnered with Bogota on other game-changing inclusive urban infrastructure projects, in alignment with our smart cities and gender priorities.

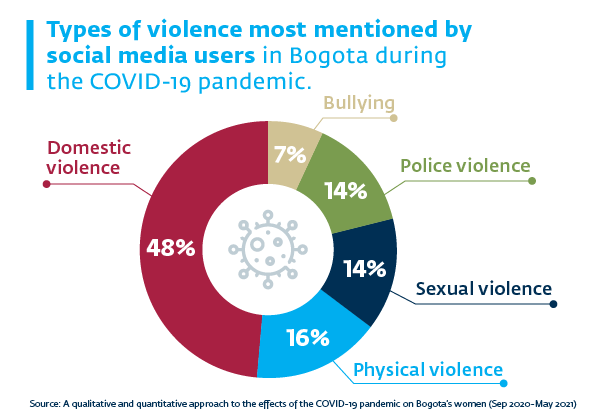

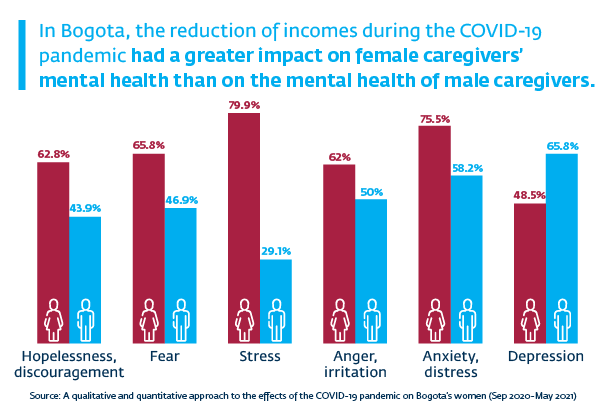

For the study, IFC leveraged an innovative “social listening” technique, which involved monitoring and analyzing millions of public social media mentions about the pandemic to understand more about the covid-related stresses faced by women caregivers by using natural language processing and machine learning. It revealed the depths of women’s struggles—lost income, anxiety, and depression, along with an uptick in domestic violence: Of the more than 500,000 mentions of violence captured, 48 percent specifically referred to domestic cases. The study also uncovered an opportunity for the city to improve digital interaction with citizens about the kinds of programs that could support them and where to access assistance. And it clearly demonstrated that women and men felt the burdens of care in different ways.

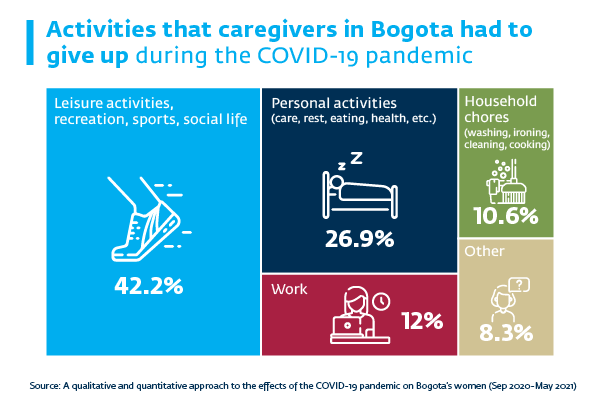

In parallel, IFC conducted a confidential phone survey, in which thousands of unpaid caregivers responded frankly to questions about what they were sacrificing. The findings were sobering: close to 70 percent caregivers reported that they were neglecting such self-care as resting, eating, and health or that they had to give up leisure-time activities.

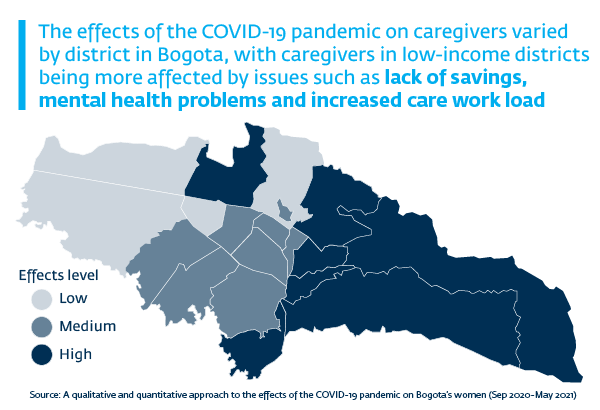

After completing both the social listening project and the phone survey, IFC analyzed the data collected through a gender lens, to generate specific insights such as mapping out district-level disparities in the degree of difficulties faced. The evidence proved what city officials had suspected—that the largest clusters of profoundly impacted women live in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

Officials said that this highly detailed, hyper-local data will help with more effective policymaking. “The updated data contributes to one of the mayor’s main commitments, the City Care System,” noted Diana Rodríguez Franco, Secretary of Women´s Affairs of Bogota. “Having district-level information helps legitimize the decisions made [about where and how to target resources].” The Secretariat of Women’s Affairs and the Under Secretariat of Citizenship Culture have used the results for district level diagnosis and improving their digital campaigns.

It’s an important example of how cities can use information-gathering techniques such as social listening and digital tools for the public good. They are the basis for tracking sensitive topics like gender-based violence. They give government officials a way to connect with their citizens–all of whom have stories to tell. And they help policy makers become better informed about the realities that frame people’s day-to-day, allowing for service provision refinements that directly address needs and improve lives.

Click here to learn more about IFC’s work on addressing community concerns.

Related Content

No Deal or New Deal? 3 Factors for Unlocking Digital Opportunities for Local Youth and Women

Gender

Local Government and Development

Why the infrastructure industry should create more opportunities for women

Gender

Local Government and Development

Equality to Safeguard the Environment: How Women Improve the Environmental Performance of the Minerals Sector

Gender

Local Government and Development

Leave a Comment

- IFC

- IFC Sustainable Infrastructure Advisory

- IFC Infrastructure

- IFC Oil, Gas and Mining

- IFC Performance Standards

- IFC Sustainability

- IFC Telecoms, Media, and Technology

- IFC Financial Valuation Tool

- PPP Knowledge Lab

- World Bank Open Data

- World Bank Extractive Industries

- GOXI Sharing in Governance of Extractive Industries

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!